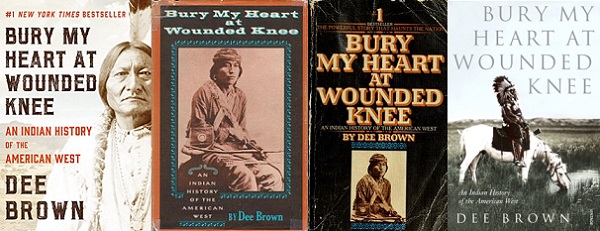

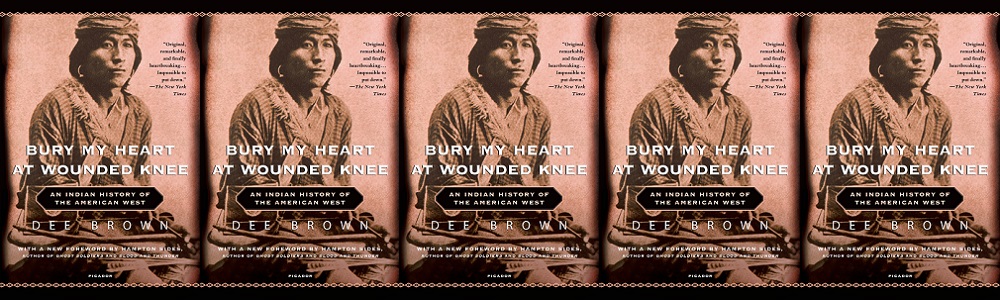

The book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West is described by Macmillan Publishers as “Dee Brown‘s eloquent, meticulously documented account of the systematic destruction of the American Indian during the second half of the nineteenth century.” The Encyclopedia of World Biography quotes Brown‘s book as an “invaluable and extensive impact on how Native American history is viewed” while National Public Radio (NPR) reviewed the book in 2019 as telling a “story of U.S. government betrayal, forced relocation and massacres.”

The book is told from several firsthand points-of-view of members of the distinct native cultures impacted by the incoming United States government composed largely of Europeans. After giving a brief overview of the United States and native population from the Christopher Columbus landing in 1492 to 1860, the novel gives extensive tales of American encroachment on native lands and against native populations. The point-of-view relies on direct quotation through the Wounded Knee Massacre of December 1890.

The message book is not without those wishing for a fuller articulation of the American point-of-view. While the book touches on elements of the American Civil War, for example, there is other history of the United States at the time. The notion of Manifest Destiny was discussed strictly in its effect on broken promises in furtherance of land and cultural encroachment. That said, the book is subtitled as an “Indian History”. The David Treuer book The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present tackles issues he, Treuer, had with Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West among at least some surviving natives.

There is merit to the effort of Dee Brown from Alberta, Louisiana aiming to tell the first-person story of native populations affected by their interactions with the European counterparts that in large part established a new government in North America. There are issues on multiple levels as well, which tempers my overall grade for the book. I grant Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West by Dee Brown 3.75-stars on a scale of one-to-five stars.

Matt – Saturday, August 12, 2023

(Ojibwe American writer, critic, and academic David Treuer wrote the 2019 book The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee).

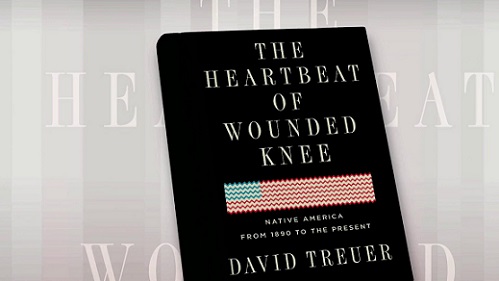

(Ojibwe American writer, critic, and academic David Treuer wrote the 2019 book The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee). (An image of the 2019 book The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee).

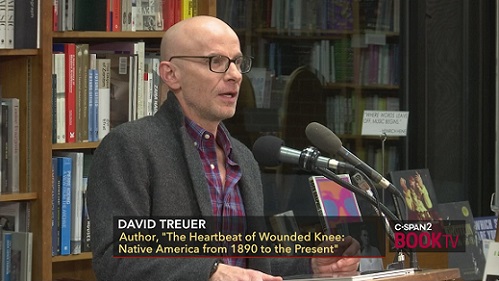

(An image of the 2019 book The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee). (Ojibwe American writer, critic, and academic David Treuer on

(Ojibwe American writer, critic, and academic David Treuer on  (Ojibwe American writer, critic, and academic David Treuer wrote the 2019 book The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee).

(Ojibwe American writer, critic, and academic David Treuer wrote the 2019 book The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee). (Ojibwe American writer, critic, and academic David Treuer).

(Ojibwe American writer, critic, and academic David Treuer).